BREED DESCRIPTION

By E.F. Watkins

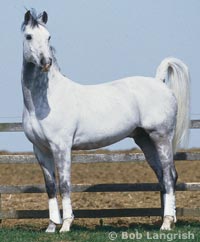

You know horses, and you could swear you're looking at an Arabian. But there's something about this one, however, that's a little different. He has the same small, chiseled head, the graceful, curved neck, the somewhat short back and the high, proud tail carriage. Still, he's tall for an Arabian, bigger-boned and more substantial. He's a beautiful horse, but what is he? Some kind of cross, perhaps?

If you've never seen a Shagya before, you have plenty of company. This striking animal is still rare in the United States, where there are only about 20 active breeders of purebred Shagyas. They make up a passionate group, however, and are eager to enlighten their fellow Americans about the horse's sporting potential and long, colorful history.

The wellspring for purebred Shagya Arabians is still Babolna, Hungary. Founded in 1789, the Babolna stud originally produced high-quality horses for the formidable Austro-Hungarian cavalry, and many of the early broodmares had served as army horses. In 1816, the stud began injecting new blood by importing purebred Arabian stallions of desert breeding and crossing them with Arabian-looking mares that had Hungarian, Spanish or Thoroughbred blood.

The Arabian stallion Shagya came to Babolna from Syria in 1836. Descended from the Koheilan/Siglavy strain, Shagya was big for an Arabian — almost 16 hands — and was a distinctive cream color. He stood at Babolna until 1842, during which time he founded a breed all his own. His male descendants continue the Shagya dynasty today at studs all over Europe.

At the end of World War II, General George S. Patton brought about 20 Shagyas, along with other "rescued" European horses, from Czechoslovakia to the United States. The Shagyas were officially classified as "Arab kind," because the Americans did not recognize them as a special breed.

Three mares ended up on the 30,000-acre Montana farm of Countess Margit Bessenyey, granddaughter of Marcus Daly, the Anaconda Copper Company tycoon, and daughter of a Hungarian count. The countess acquired the horses in an attempt to preserve her Hungarian heritage. She ended up breeding only one pure Shagya, the stallion Hungarian Bravo, who was registered with the Hungarian Horse Association that she founded in 1966.

When the countess died in 1985, Bravo was 24. Her will specified that 22 of her older horses be put down humanely, because she feared they would fall into abusive hands. Bravo would have died this way, and the breed would have been wiped out in this country, if not for the efforts of Montana horsewoman Adele Furby. Furby, originally a breeder of Arabians and half-Arabians, had visited the Bessenyey ranch and developed a fascination with the Shagya. When she heard about Bravo's impending doom, she asked some locals to intercede in her favor so that she could buy the stallion.

Coming to America

Once she had him, she wrote to the Purebred Shagya Society International (ISG) for more information. The group sent back word that it wanted Bravo to be the foundation stallion in the United States. Furby got the organization's approval to breed a few Arabian mares to Bravo. She also imported six more Shagyas, single-handedly reviving the breed in America. In 1986, she founded the North American Shagya-Arabian Society (NASS) as a member organization of the ISG and established stud books in this country for both Shagyas and part-Shagyas.

Bravo survived to age 28, and by that time Furby had enough of his offspring to carry on the line. Bred to eb used for riding and driving, the Shagya still derives largely from desert-Arabian-influenced, Eastern European breeds; carefully selected desert Arabian stallions are occasionally used to improve the strain.

"The breed was consolidated many generations ago, so that it consistently breeds true to type," says Furby. "The Shagyas combine the advantages of the Bedouin Arabian — elegant type, great hardiness and toughness, endurance, easy-keeping qualities and inborn friendliness to humans &3151; with the requirements of a modern riding horse — sufficient height, big frame and great 'rideability,' including excellent movement and jumping ability."

The Shagya MissionThe breeding goal, as stated by the ISG, is that "the Shagya should be beautiful and harmonious, with an expressive head and well-formed neck, a good topline, a long pelvis, a well-carried tail and strong, dry, correct legs. Free, springy, elastic and correct action in all there gaits is very important. Wither height should be at least 15 or 16 hands, and cannon bone circumference should be a minimum of 7 inches. The Shagya should be physically and mentally capable of being a completely efficient and superior family, leisure, competition, hunting and endurance horse."

Furby admits this is an ambitious goal, but one she and other breeders strive to attain. "The European warmblood breeds are quality-controlled this way in both Europe and America," she says. "The NASS is attempting to maintain a similar system."

Dr. Michael Foss of White Salmon, Washington, met his first Shagya about eight years ago on his veterinary rounds. He treated one for a client and found it "a nice horse to work with." Soon he purchased some mares from Furby and began his own breeding establishment. Today he is president of the NASS.

"I thought they were a nice, sensible horse," he says. "Also, the inspection process they have to go through for breeding approval is very important to me. There's a lot of 'genetic junk' out there. I see a lot of that as a veterinarian," he says. "I saw a chance to have some quality control, plus a nice horse to start with." Dr. Foss believes that, compared to an Egyptian Arabian, a Shagya has more substance and bone, and also a cooler temperament. "They're still alert, but a little easier to work with. Also, they're fun to take out, because people always ask me, 'What's that?'"

He says that when his gelding O'Shaunassy competes in endurance trials, people ask what kind of horse he is. Some swear he must have Thoroughbred in him, even though, this far down the line, he really doesn't.

"They recognize him as something other than strictly Arab," says Foss, "but they're not sure what else!" The unfamiliarity with the Shagya name in itself causes misunderstanding. Foss notes that, upon hearing it, many people expect a "shaggy" horse. When Karen Mullen of Pennsylvania took her two Shagya fillies to a sporthorse show in Devon, and wrote "SH" on the entry form under breed, a judge remarked that they seemed "too small for Shires."

Quality, Not QuantityOnly about 100 purebred Shagyas exist in the United States and the first American-born foals are just coming of age to show, so the breed has yet to demonstrate its full potential here. There may be fewer than 2,000 of the horses worldwide, and as Adele Furby points out, "When a group is that small, you're not likely to find many in higher levels of competition."

Nevertheless, the Shagya stallion Ghazzir made it into the top 10 in three-day eventing at the German National Championship for Young Horses in both 1990 and 1991. At 16 hands, he was the smallest in the competition, working against assorted breeds over daunting obstacles; still, he clocked the fastest time cross country.

Furby notes, "Ghazzir is not even an exceptional Shagya. The main difference was that his owner spent the money to have him trained and put in competition." Furby personally saw a Shagya compete successfully on the Grand Prix level in dressage in Germany, doing an impressive musical freestyle. Shagyas have easily kept pace with native Trakehners in an annual hunt held at the Marbach stud in Germany, and the breed already has established a worldwide reputation.

Nancy Skakel of Illinois shows her Shagyas in driving classes around the Midwest. Furby has sent her 13-year-old stallion Shandor, used primarily for breeding up until now, to an Oregon trainer to be schooled in dressage. "They have the balance on the hindquarters that is needed to elevate the forehand for dressage," she says.

While Furby believes the best way to showcase the horses, especially since they are so few in number, is to put them in competition against other breeds. But another NASS member, Carolyn Tucker of California, has been trying a different approach. In 1996, Tucker helped organize the Pacific Coast Arabian Sporthorse Classic, the first U.S. sporthorse show especially for Arabians. She saw to it that the show included a dozen events just for Shagyas, including both dressage and in-hand breed classes.

"I do a lot of my own riding and training," says Tucker. "I have several Shagyas, and I'm always competing in various disciplines." She says she started five of her horses in distance riding one mare now does mainly competitive trail riding, while another has begun dressage. Her stallion Oman and her gelding Crescendo AF have been eventing.

Tucker also finds that onlookers will question her about the breed of the horse. Crescendo, Oman's eldest son, is 16.1 hands and, she says, looks very much like a warmblood. "They're very beautiful, with a lot of charisma and lively movement," she says, "but they're also very calm. That draws a lot of attention at a show. There may be 200 horses around, but they'll be absolutely calm."

Like Furby, Tucker originally bred pure Arabians, and finds the Shagya's temperament very different. "That's the Hungarian influence," she says. "They're more tolerant and willing, and less reactive. It makes training faster, easier and safer." Still, she points out, the Shagya retains the legendary Arabian "smarts." "If you teach them something, and they get it the first time, you don't need to repeat it. And if they get in a jam, they don't overreact, as some horses do. You have to be around them awhile to appreciate them. That's why we have to get them out where people can see them."

Oman has been approved for 100-day performance testing by the German-based International Sport Horse Registry. If he passes the test, he will receive a "Lifetime Breeding License" for use in improving the Oldenburg warmblood line. All of Oman's male ancestors have gone through this testing in Germany, but he will be the first U.S. Shagya to do so. Shagyas have also been used in Europe to improve other warmbloods, such as the Trakhener line.

To keep the breed's standards high, ISG judges visit the United States every two or three years to tour the breeding farms and inspect the new foals. All Shagyas can trace their ancestry back to only about a dozen stallions, including the original Shagya, Gazlan, O'Bayan, Koheilan, Siglavy, Siglavy Bagdady and Dahoman. Furby points out, however, that the influence of the dam also must be considered, and a horse is not judged harshly if he does not resemble the sire line.

She and some other American Shagya breeders have visited the European stud farms to become more knowledgeable about the horse's history. She explains, "It's not a show-horse Arabian or an imitation warmblood. It's more an historic breed that can do modern things."

A qualified international Shagya judge, Furby served in that capacity for one show in Hungary that featured horses from all over Europe. She says, "I've seen the growth of the breed there. It will be a long time before we're at that point."

If anything hastens the rise of the Shagya's popularity, it will be the enthusiasm of the owners and breeders. Furby has worked with the animals for more than 10 years now and remains passionate about them. "These horses are so well built, with such good dispositions, that they are incredibly versatile. They can do a number of things and do them well. I don't even care to ride other breeds now, I'm so spoiled."

Dr. Foss can think of only one drawback to owning a Shagya — "You know you've got a nice horse, but no one else knows about it!"

For more information about the Shagya Arabian, contact Public Information Officer Gwynn Davis at the North American Shagya-Arabian Society, RR 1, Box 822, Clinton, IN 46842; 317-665-3851.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home